FOREWORD

Hand-drawn Disney animation holds a unique place in the history of modern art and popular culture. The work showcased in this book comes from Disney artists and animators who brought grat performances to the screen by drawing with emotion, sincerity, and intensity. Knowing full-well that many of these sketches would be seeen only in pencil tests and preliminary screenings - or never at all- the artists "drew from within themselves" onto a sheet of papaer or a digital tablet. In the process, they created incredible works of art in their own right.

While reviewing a few of his own animation drawings made for Peter Pan. Frank Thomas, one of Walt Disney´s original "Nine Old Men", once explained to me that he and hid collagues never thought of their drawings as final works of art. "we were working to communicate the story", he said, "and we were thinking about what the character was thinking and feeling not only in this moment, but in the one before it and the one after it. We weren´t thinking about making drawings. We were thinking about telling a story".

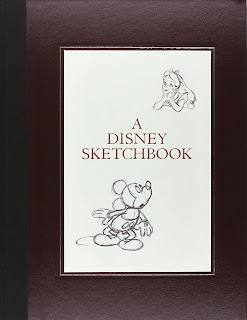

Unprocessed, uniked, unpainted, and un-rendered, a selection of Disney drawings is reproduced here as if drawn into a sketchbook. This Shetchbook celebrates the very early statges of Disney filmmaking, in witch the human touch defines both a chracter´s performance and its role in telling a story. Drawings used for story and visual development, animation thumbnails, rought animation drawings, layout drawings, and other works have been organized in a rought chronological order, with the knolegde that many of these films and their producction statges often overlapped.

Ken Shue Vice President, Disney Publishing Global Art Development Glendale, California

INTRODUCTION

Every drawing in this collection represents a step in a process of discovery Like other fine artists, the Disney animators, designers, and sKOry artista whose work appears in this anthology didn't know exactly what their drawings would lvok like until they were finished, but they knew what those drawings had to do and say. The rough, often tentative, lines show the artists exploring and discovering the best way to present a character at a specific moment in a story The storyboard panel by Bill Peet from The Jungle Book is one of many perhaps dozens, the great story artist drew trying to find the poses for Mowgli and the monkeys that communicated the key information in the scene most clearly In carlier versions, Mowgli's expressicon would have been different. The in nd branches would have been in different positions. Peet drew and rede until he had gotten all the entertainment potential out of the moment thit be could. Other artists and Walt Disney would have examined Peet's storybounds and made suggestions that led to new drawings, which were clearer or mere dramatic or funnier. Looking back over the sketches he made when he was designing Beast, Glen Keane commented, "When you design a character for a Disney fairy tale, its going to become the definitive design for that character, so you don't want to hack something out. I needed to put in the kind of care I felt it warranted if its going to live on in history as the Beast." As there was no model for what Beast should look like, Keane initially experi- mented with funny horns and ears. But they made the character look like an alien who didn't fit into Belle's world. He started over, studying animals in a Z00, and combining elements of a gorilla, bison, wolE, lion, bear, and wild boar into the Beast that Belle learns to love. Animators find inspiration everywhere. Ollie Johnston realized how Fauna in Sleeping Beauty would act when he watched a little old lady on vacation i a hotel agree with everything her friends said-even when they contradicted each other. For One Hundred and One Dalmatians, Marc Davis wanted to make Cruella De Vil move "like someone you wouldnt like.

But translating an inspiration into drawings that come to life on the screen in- volves work, exploration, experimentation, frustration, and more work. As a young artist, Brad Bird observed how Milt Kahl approached the animation of Madame Medusa in The Rescuers. "He would draw a page of slight variations on a single pose. If you just glanced at the page, there might be twelve or fifteen poses that looked identical," Bird recalls. "But if you examined them closely, you'd see all these little shifts: the shoulder would be a little higher, the twist of the body would be a little more pronounced, then a little less; fingers on the lips, knuckles on the lips, wrist on the lips; head propped up, head propped down. He would explore, pick one pose, then move on to the next one, which might occur a second later, and do the same thing, He was constantly searching for the best possible graphic statement." Walt Disney advanced the art of animation by giving his animators the time they needed to explore and experiment. Grim Natwick, who animated Snow White, said, "They allowed me two months of experimental animation before they ever asked me to animate one scene in the picture. Disney had only one rule: whatever we did had to be better than anybody else could do it, even if you had to animate it nine times, as I once did." More than eighty years after Mickey Mouse whistled and danced his way into audience's hearts in Steamboat Willie, the artists at the Disney Studio continue to explore and experiment, working to find the best way to present the story they're telling. They may now use pencils or digital tablets, but the process remains the same. Work and rework each image until it's as perfect as it can be, then make it better. The drawings in this collection offer readers who love the Disney films insights into the process of the creation of their favorite characters.

Charles Solomon Animation critic and historian